Get Healthy!

- Dennis Thompson

- Posted March 22, 2023

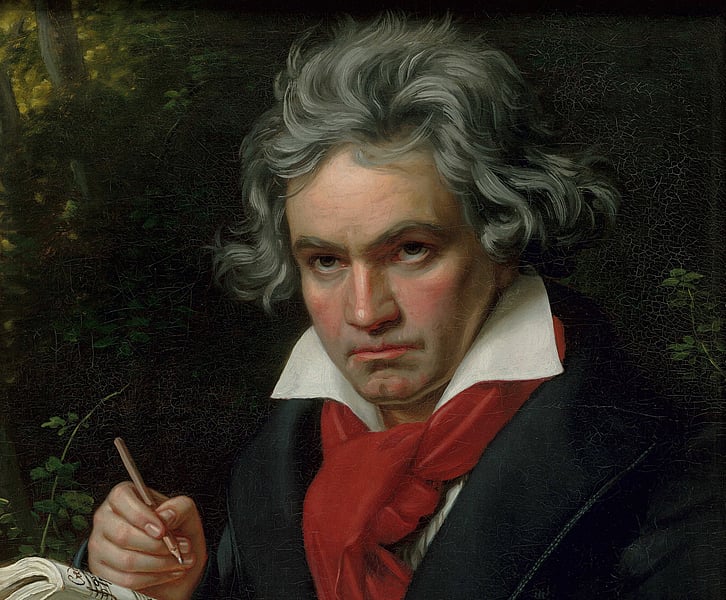

From a Lock of Hair, Beethoven's Genome Gives Clues to Health, Family

Genetic analysis of Ludwig van Beethoven's hair has provided new clues into the cause of the great composer's death in 1827 -- as well as evidence of a family scandal.

The analysis revealed that Beethoven suffered from a hepatitis B infection that could have contributed to his death from liver disease.

Researchers found DNA evidence of hepatitis B virus in a lock of hair taken from Beethoven's body shortly after his death in 1827, according to the report published online March 22 in Current Biology.

The investigators also found evidence of a strong genetic predisposition to liver disease in Beethoven, said co-researcher Dr. Markus Nothen, a professor with the University Hospital of Bonn's Institute of Human Genetics, in Germany.

"We believe that the liver disease arose from an interplay of genetic disposition, a well-documented chronic alcohol consumption, and hepatitis B infection,"Nothen said in a Tuesday media briefing.

But the researchers found they could not match Beethoven's genetic relationship with five Belgian and three Austrian descendants bearing his name, suggesting that a child born of an extramarital affair occurred somewhere in his direct paternal line.

"You cannot rule out that Beethoven himself may have been illegitimate,"said lead researcher Tristan James Alexander Begg, a doctoral student in archaeology with the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. "I'm not advocating that. I'm simply saying that's a possibility, and you have to consider it."

Unfortunately, the researchers did not obtain from Beethoven's hair the prize they actually sought -- a genetic explanation for the composer's well-known progressive hearing loss.

The scientists looked for genetic signs of several different potential causes of deafness, including otosclerosis and Paget's disease of bone, but "we didn't see evidence for a monogenic cause,"Begg said.

In this eight-year effort, the researchers analyzed about 10 feet of preserved hair drawn from five separate locks, all of which date from the last seven years of Beethoven's life.

From locks of hair, clues to cause of death

Even with all this work, the researchers were only able to map two-thirds of Beethoven's genome, Begg said.

Hair degrades more quickly than bone, making it "really hard to get enough DNA from such a sample to assemble a genome,"said senior researcher Johannes Krause, director of archaeogenetics with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

In a way, Beethoven himself commissioned the work performed by these modern scientists, as a result of his well-documented health troubles.

Beethoven started losing his hearing in his mid-to-late 20s. It is generally believed Beethoven composed some of his most famous works, including his Ninth Symphony, after he'd become completely deaf.

Beethoven also suffered from debilitating gastrointestinal (GI) problems from at least age 22, characterized mainly by abdominal pains and prolonged bouts of diarrhea, the authors said in background notes.

And in the summer of 1821, Beethoven began to show signs of liver disease when the first of at least two attacks of jaundice occurred. Experts believe this liver disease eventually led to his death at age 56 on March 26, 1827.

The day after his death, two of his associates found a remarkable document stored in a hidden compartment in his writing desk.

The letter from Beethoven to his brothers, written in 1802, described his increasing deafness and how it had led him to contemplate suicide. It included a request that upon his death, his disease be described and made public.

The letter, known as the "Heiligenstadt Testament,"kicked off what has become centuries of lively debate over Beethoven's health problems.

The researchers gained access to eight separate locks of hair attributed to Beethoven, and soon found that three of the locks did not actually come from the composer.

But no clues to early deafness

For example, the "Hiller Lock"actually originated from a woman with genetics highly prevalent among Ashkenazi Jews, the study authors said. This lock was once believed to have been taken from Beethoven's head after his death by 15-year-old musician Ferdinand Hiller.

Samples from this lock had earlier been used by other researchers to argue that lead poisoning had contributed to Beethoven's health problems. "We now conclude that these findings do not apply to Beethoven,"the researchers wrote.

The five legitimate locks -- the Muller, Bermann, Halm-Thayer, Moscheles and Stumpff locks -- were used to craft a genetic portrait of Beethoven.

Below is a photo of the Moscheles lock of hair:

The Moscheles Lock, with inscription by former owner Ignaz Moscheles. Image: Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San Jose State University

consumer.healthday.com

The Moscheles Lock, with inscription by former owner Ignaz Moscheles. Image: Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San Jose State University

consumer.healthday.com

The genetics did not reveal a clear hereditary explanation for either Beethoven's deafness or his GI problems, the researchers reported.

But the Stumpff lock, taken shortly after Beethoven's death, contained genetic evidence of a hepatitis B infection.

"That tells us that in the last few months before his death, he was infected with hepatitis B virus,"Krause said. "It could have been also present earlier."

The hepatitis B likely combined with other genetic risk factors and Beethoven's self-documented drinking to damage his liver, leading to his death, the researchers concluded.

"We cannot say definitely what killed Beethoven, but we can now at least confirm the presence of significant heritable risk, and an infection with hepatitis B virus,"Krause said in a news release. "We can also eliminate several other less plausible genetic causes."

An illegitimate child in the family?

Analysis of genetics from living relatives -- some of whom share a paternal ancestor with Beethoven from the late 1500s and early 1600s -- revealed no match with the Y chromosome found in the authentic hair samples, the findings showed.

This is likely the result of a child resulting from an extramarital relationship somewhere in either Beethoven's generation or the seven generations preceding the composer, the researchers said.

This event probably occurred between the conception of Hendrik van Beethoven in Kampenhout, Belgium, in 1572 and the conception of Ludwig van Beethoven seven generations later in 1770, in Bonn, Germany, the study authors noted.

The research team plans to make all its genetic data on Beethoven publicly available.

"If in the future people maybe find other disease genes, they could actually quiz the genome from Beethoven now for those genes maybe being present,"Krause explained.

"It is also possible that other groups will study some of the other locks that exist,"Krause added. "We looked at eight, but there are another at least 24 that exist."

However, the researchers said such rich findings likely wouldn't occur when plumbing the genetics of other historical figures who left behind DNA samples.

That's because most great men and women don't typically have a history of strange health problems and mixed paternity, Begg and Nothen said.

"Like my 23andMe results and that of most people on the planet and therefore most historical figures, there is going to be nothing wrong with them,"Begg said.

"Beethoven also is kind of unique because of the enormous literature on his health problems,"Nothen added. "So it was really, I think, a unique chance to use modern genetic methods to add something. I don't know any historical person with a comparable literature on health and diseases."

More information

The Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies at San Jose State University has more about the life and work of Beethoven.

SOURCES: Markus Nothen, MD, professor, University Hospital of Bonn's Institute for Human Genetics, Germany; Tristan James Alexander Begg, doctoral student, archaeology, University of Cambridge, England; Johannes Krause, PhD, director, archaeogenetics, Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, Germany; Current Biology, March 22, 2023, online